The great Indian robbery

At least $500 billion, or Rs.22.5 lakh crore, has been spirited out of India illegally to foreign bank accounts over the six decades since Independence. This is the key finding of a comprehensive study on the Drivers and Dynamics of Illicit Financial Flows from India: 1948-2008 conducted by the US-based Global Financial Integrity (GFI). This staggering sum amounts to almost half of India's $1.3-trillion GDP and is parked in accounts across exotic locales such as Switzerland and the Cayman Islands. The identities of the owners of this loot are unknown, as of now. But the sanctuary of ignorance has begun, at long last, to crumble.

On January 17, a former employee of a prominent Swiss Bank handed over a list of 2,000 people suspected of tax evasion to WikiLeaks chief Julian Assange. The news that he will soon reveal all the names, at least some of whom are likely to be Indian nationals, sent a shiver down Delhi's spine-the Capital already reeling under a string of scams and corruption allegations. Meanwhile, a PIL filed in the Supreme Court by a group of eminent citizens, including Ram Jethmalani, KPS Gill and Subhash Kashyap, to bring back black money stashed abroad, has brought back into focus the list of the names of 50 tax evaders that German authorities had handed over to India in 2008.

The Supreme Court's comments were scathing. "It is a pure and simple theft of the national money. We are talking about mind-boggling crime. We are not on the niceties of various treaties," said Justices Sudershan Reddy and S.S. Nijjar. On the specific matter of the 50 names, the bench said, "What is the difficulty in disclosing the information?" The justices caused Solicitor General Gopal Subramaniam more discomfort, and the Government further embarrassment, when they remarked, "Why are you limiting the matter to the Liechtenstein bank only?"

The transfer of these illicit funds supported by soft governments who seem indifferent to the loot of national wealth violate a host of criminal and civil codes, tax laws, customs regulations, VAT assessments and banking regulations. These funds may have been kickbacks for arms deals, bribes for awarding contracts or corporates skimming off their profits and diverting them into foreign bank accounts. There are at least 40 destinations that aggressively solicit such funds. The most popular destinations are Switzerland, Luxembourg, Liechtenstein, Channel Islands and the Bahamas.

The GFI study estimates that roughly 72.2 per cent of the Indian economy's illicit assets are held abroad. The size of India's underground economy is estimated to be at least 50 per cent of its GDP or about $640 billion (based on the $1.28 trillion GDP in 2008).

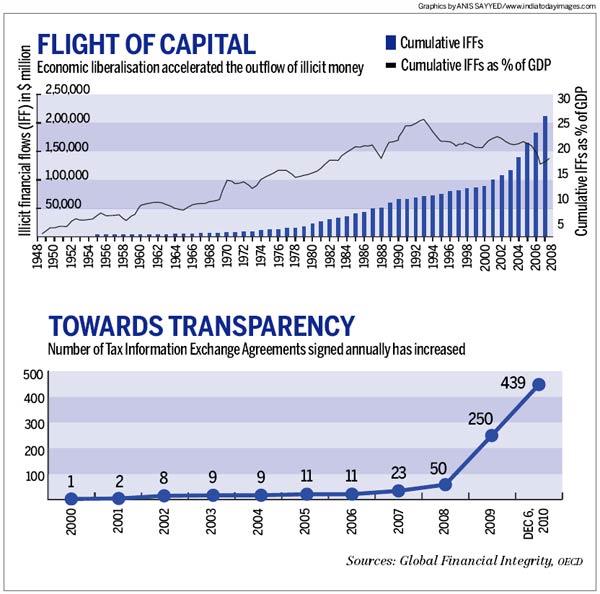

Economic liberalisation has only accelerated the outflow of illicit money. Says Raymond W. Baker, director, GFI, "Opportunities for trade mispricing have grown and expansion of the global shadow financial system accommodates hot money, particularly in island tax havens. Disguised corporations situated in secrecy jurisdictions enable billions of dollars shifting out of India to 'round-trip', coming back in short-term and long-term investments, often with the intention of generating unrecorded transfers again in a self-reinforcing cycle."

Sometimes, the money is physically transferred abroad. The CEO of a Mumbai-based equity firm says that the money is flown abroad in "special flights" or chartered aircraft out of Mumbai and Delhi airports to Zurich. Perhaps this is one reason behind the demand for private planes. The classic modus operandi continues to be the underinvoicing or overinvoicing goods and services. Swiss banks remain the top destination for illegal funds because of their strict secrecy laws. When the Obama administration began a crackdown on illegal accounts in March 2009, says an Indian CEO, Swiss banks unveiled the ultimate secrecy tool, an insurance wrapper with even stricter secrecy clauses.

It's not just secrecy. Says a senior Income Tax official, "One problem with the Swiss banking law is that they require dual criminality to be proved before revealing information. Tax evasion is not a criminal offence in Switzerland, even though it is a criminal offence in India. So to get information, we have to present a case for money laundering, corruption or drug running which is much harder than a straightforward tax evasion case."

The Opposition BJP had earlier raised the issue of black money abroad in the run-up to the 2009 General Election. At that time, the issue did not capture the popular imagination and Prime Minister Manmohan Singh's image of honesty and integrity saw the UPA through. Two years later, the prime minister's credibility is battered by a string of scams. Says BJP spokesman Ravi Shankar Prasad, "What is the problem for the Congress in revealing the names? Why is this dogged refusal to reveal names of those who have accounts abroad? The country has a right to know and expects the names to be made public." Adds BJP President Nitin Gadkari, "Any reluctance in declaring the names of Swiss bank account holders will simply raise doubts about the integrity of people at the helm."

The international environment has turned decisively against banking secrecy and opaque cross border financial dealings. The first push in this direction came in the aftermath of the 9/11 terror attacks in the US. The US Patriot Act, signed into law in October 2001, devoted an entire section to the prevention of money laundering. The new law required a regular sharing of information between financial institutions and law enforcement agencies. It mandated US financial institutions to implement strict know-your-customer norms and prohibited any dealings with shell banks-those without a branch or an associate bank in the US. Other countries passed similar laws but the focus remained mostly on tracking terror funding, not tax evasion.

The second and more recent push came in the aftermath of the outbreak of the global financial crisis in 2008. Public anger at rich financiers and bankers, who were alleged to have precipitated the worst economic crisis in six decades, many of whom suspected of having deposited their money in tax havens overseas, forced Western governments to initiate a crackdown. The communique, issued after the London meeting of the G20 on April 2, 2009, made it clear that it was going to be much harder to evade taxes by sending money overseas. "We agree to take action against non-cooperative jurisdictions, including tax havens… We note that the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has today, published a list of countries assessed by the Global Forum against the international standard for exchange of tax information," it said. India was a signatory to the G20 communique.

Forty countries were identified in a "grey list" of tax havens and (non-cooperative) financial centres that had agreed to internationally accepted tax standards, but had not substantially implemented them. Switzerland and Liechtenstein were named in that list, creating enormous pressure on them to comply with international standards on sharing tax information.

The OECD's Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes, first established in 2000, underwent serious restructuring in September 2009 at the behest of the G20. It was the chosen body to coordinate multilateral efforts at increasing transparency of tax havens and other secretive financial centres. The Forum now has 95 member countries and includes all G20 countries, all OECD countries and all major financial centres. The G20 reaffirmed its support to the Global Forum at Seoul in November 2010. "We fully support the work of the Global Forum… and welcomed progress on their peer review process, and the development of a multilateral mechanism for information exchange which will be open to all interested countries.… We stand ready to use countermeasures against tax havens."

Only 70 Tax Information Exchange Agreements had been signed between countries in the eight years between 2000 and 2008 while 500 new agreements were signed between 2009 and 2010. The pressure from G20 forced countries like Switzerland and Liechtenstein to sign information sharing agreements in order to get off the "grey list". The Forum, as a point of principle, requires "exchange of information on request where it is "foreseeably relevant" to the administration and enforcement of domestic laws of the treaty partner" and says that there can be "no restrictions on exchange caused by bank secrecy or domestic tax interest requirements."

At Seoul, OECD Deputy Secretary-General and Chief Economist Pier Carlo Padoan presented details of money recovered since April 2009 to G20 finance ministers. "Germany has already collected $5.4 billion from overseas evaders. The UK has collected an extra $810 million and expects this figure to increase to at least $11 billion. France has collected an extra $1.3 billion, Italy $6.7 billion and Greece estimates it could collect an extra $48 billion in revenues," he said. Padoan referred to India among the group of countries that "are also using these initiatives and will see significant increases in revenues from tax evaders who have decided to come clean".

India is one of the 15 members of the Global Forum's top advisory body. India has not yet signed any Tax Information Exchange Agreement which explains why it has not submitted any data on recoveries to the Global Forum. "We are in negotiations with 22 countries to ink the Tax Information Exchange Agreements. Agreements with three countries are at an advanced stage," said Sudhir Chandra, chairman, Central Board of Direct Taxes. An agreement with Switzerland, the centre of all attention, is still in process. But why has the Indian Government taken so long to ink even one Tax Information Exchange Agreement when the rest of the world has moved at a rapid pace?

Getting the money back matters. Says BJP leader L.K. Advani, "The money could satisfy India's infrastructure needs." He is right. The Planning Commission had set a target of $500 billion for investment in infrastructure between 2007 and 2012.

The Supreme Court and the Opposition have increased the pressure on the Government. However, its continued inaction suggests that the UPA would prefer to remain as secretive as the proverbial Swiss Bank.

You May Be Interested IN