The Man Who Was Seen Too Much: Amitabh Bachchan on Film Posters

The film poster as a publicity icon has been around for most of the 20th century, creating its own parallel universe and history alongside that of celluloid. Along with billboards, posters in India have played a pivotal role in creating a colorful and vibrant buzz around cinema.1 As film memorabilia, the poster operates in public memory literally like a device that triggers off a series of associations linked to cinema, stars, stories, public spaces, events, music and more.2 This essay attempts a journey into the recent past to look at a collection of posters that showcase one of Hindi cinema’s biggest stars, Amitabh Bachchan, during the most significant period of his career. I undertake this journey with knowledge of the films and the position the star had in that period. While we may now recognize the importance of the poster as an ancillary production unit of the film industry, a close look at posters of a particular historical moment which got identified with a star can reveal the complex mechanisms of a visual culture associated with cinema. A relational reading across a set of posters displaying one star’s iconographic journey can help us understand the film industry’s negotiation of the box office and the way star value was assessed. An analysis of these posters will also reveal the tussles of the 1970s and 80s when a superstar such as Bachchan was operating alongside the multi-star form, generating interesting tensions within the film industry.

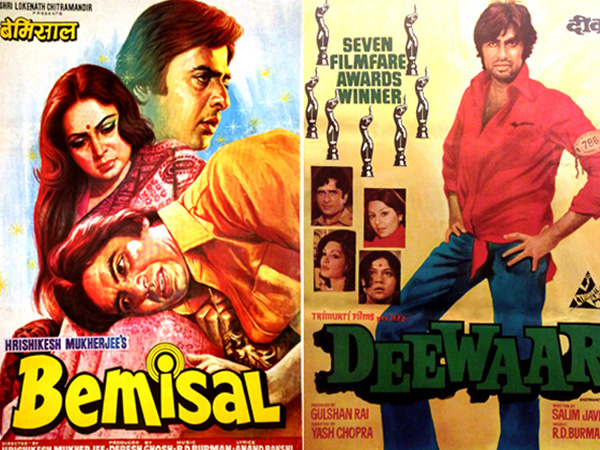

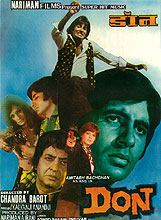

Simply put, film posters are frozen images of narrative cinema whose primary object is to arouse the curiosity of potential spectators, to persuade them to enter the movie theatre. These posters are essentially created just before the film is ready for distribution. As a publicity icon, the poster is meant to convey the theme, the genre, the locations, the emotional contour and the primary star cast of the film. Don was released in 1978 at the peak of Bachchan’s career. In the poster of the film presented here as fig. 01, the actor is reproduced thrice in the frame. We see him in action right in the centre. We see Helen on the left as she pours a drink for the actor. Finally, the typical Bachchan face is profiled on the right. The bottom center shows Zeenat Aman, pointing a gun at the spectator. This poster of Don is a clear example of how cinematic elements get distilled into a set of frozen visual codes through which we imagine the film. The three avatars of Bachchan in the poster convey action, dramatic interiority and seductive charm. Helen’s presence in the poster conveys the possibility of a cabaret, while the presence of female oriented action is conveyed through Zeenat Aman, sporting a short haircut, a determined expression on her face as she points the gun at the viewer.

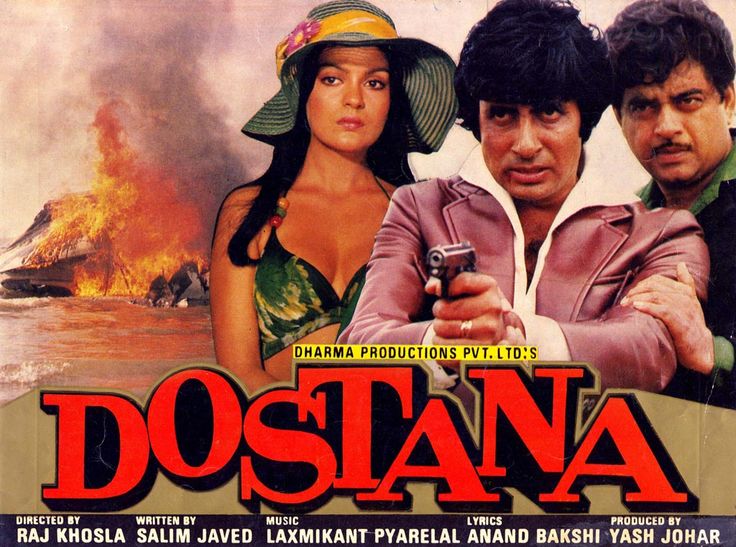

In the days of Amitabh Bahchan’s stardom, film posters were the most important vehicle for film publicity along with official theatrical trailers and printed advertisements in newspapers and magazines. Television made its entry as a domestic item only in the early seventies and was controlled entirely by the government until the 1990s. Most of TV programming was still predominantly pedagogical in nature and film content was only allowed as part of the Sunday feature, or as short programmes on film music. No advertising was allowed on television and therefore the medium was not available for filmmakers to publicize their films. It was the printed poster, plastered on walls, buses and trains that operated as the primary pre-release publicity vehicle. As a major component of visual culture, the film poster added tremendous signage to street life and created a parallel discourse for the marketing of films. This period also saw a combination of the hand painted poster and the “cut and paste” form. For the hand painted poster, the artist painted the poster design on canvas on the basis of stills provided by the producer. The “cut and paste” method on the other hand was a combination of photographic cut outs and painted embellishments. In both versions, a master copy was prepared by hand, shot on camera and then the photographed image was used for mass printing.3 The cultural iconography of the poster as we will see always relies on both cinematic and extra cinematic discourses to evoke a form where industrial practice, spatial and cultural value, historical circumstances, questions of stardom and melodrama come together. While these elements are central to the films themselves, the posters not only offer a parallel discourse, but also directly highlight changes in the film industry, making certain tensions more visible. These tensions include conflicts between stars, between the creative vision of directors and the publicity drive of producers. One could then treat these posters as documents of contradictions, absences, and subterranean narratives of the film industry, where the visible, the invisible, and the conflictual, jostled for space.

The Arrival of Amitabh Bachchan

Amitabh Bachchan’s “superstar” status has been documented considerably, both by journalists and by academics.4 Imagined as the “angry man” in the 1970s by the writer duo Salim Khan and Javed Akhtar, Bachchan found himself catapulted into a strikingly new cinematic imagination of political and social turbulence. Writing about the actor in 1996, journalist Avijit Ghosh sums up the moment well: “The hollowness of official slogans like Garibi Hatao ["Eradicate Poverty"] reflected itself everyday in rising prices, growing unemployment and rampant corruption. Cynicism bred easy, accentuated further by the State’s insensate treatment… of the JP student movement. But there was also a sense of helplessness that spawned a bitter and impotent rage. It simmered until Amitabh Bachchan showed how the underdog and the underprivileged could strike back. When his clinched fist and baritone boom burst with primeval intensity, in darkened cinema halls smelling of sweat and urine, a nation’s eager fantasy came to fruition.”5 Bachchan’s image as the “angry man” circulated widely and gained the currency of a modern myth. Never before had an actor had this kind of presence, embodying the social and political turbulence of his time. This iconic presence of a single actor also signified major transformations that were taking place in the film industry from the 1970s onwards, an issue that is not always highlighted in existing accounts of Amitabh Bachchan.

The most prevalent industry discourse positioned the star as a “complete actor.” 6 This term essentially referred to Bachchan’s ability to handle comedy, action, dance, drama and romance. The process that went into the making of the “one man performer” who could do it all himself slowly ushered in a marginalization of comedians and several other peripheral characters who had traditionally provided interruptive relief, on the margins of the main story. Amitabh Bachchan as we all know was a versatile actor who could move easily between brooding anger, comedy, romance and most of all action. Bachchan’s stardom coincided with a particular kind of professionalization of action in the industry with stunt directors creating their own space. Bachchan himself became well known for doing his own stunts, something that was taken note of and appreciated by many action directors. M.B Shetty who had simultaneously emerged as the industry’s most highly rated stunt director said in an interview, “Show me one actor anywhere in the world who can do the kind of stunts Amitabh does without a double and I’ll give you my right arm.”7 Bachchan’s achievement with stunts was widely reported in the popular press and contributed profoundly to the consolidation of his masculinity.8 Bachchan’s limited but well known dancing steps became a familiar presence in several of his films, emerging as the quintessential Bachchan style. Most of all the female lead became marginal as Bachchan reached the position of the highest paid actor in the film industry. The idea of the “complete actor” therefore indicated an overwhelming consolidation of industrial practices around one figure. It is not surprising that the label of “one man industry” was used to identify Bachchan’s presence and power.9 Films sold because of his name and presence in the film. The actor was known to move at times between the shooting of three different films, all during the course of a single day. This mythology of stardom can be accessed in the Bachchan posters and reveal carefully worked out iconographic techniques. This was also a marketing strategy in which the industrial landscape, the turbulent political milieu of the period, Bachchan’s new style of acting, and stardom, came together.

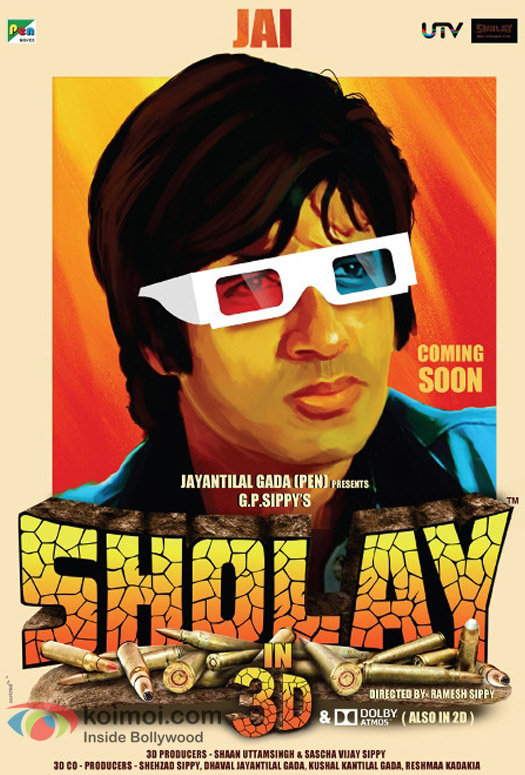

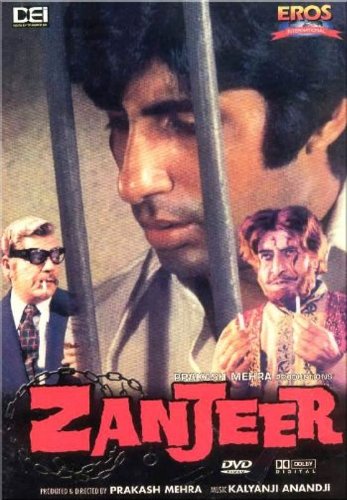

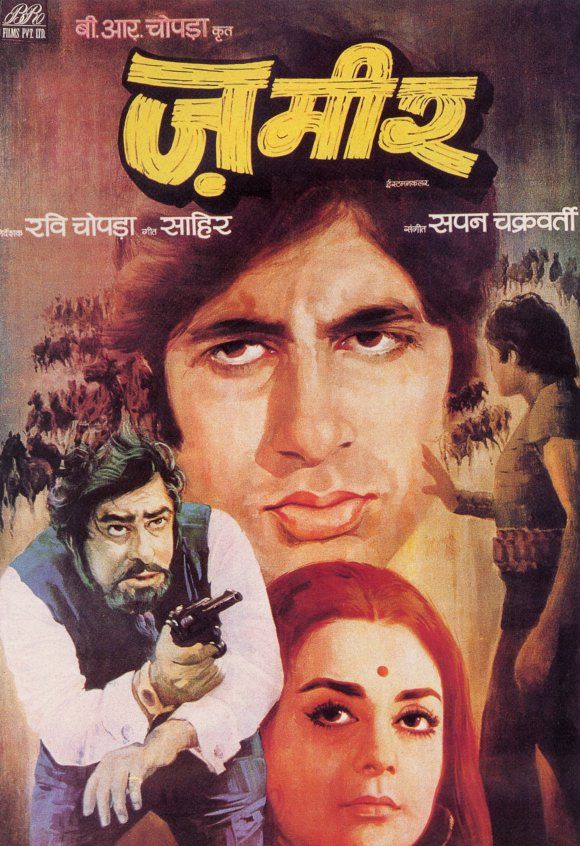

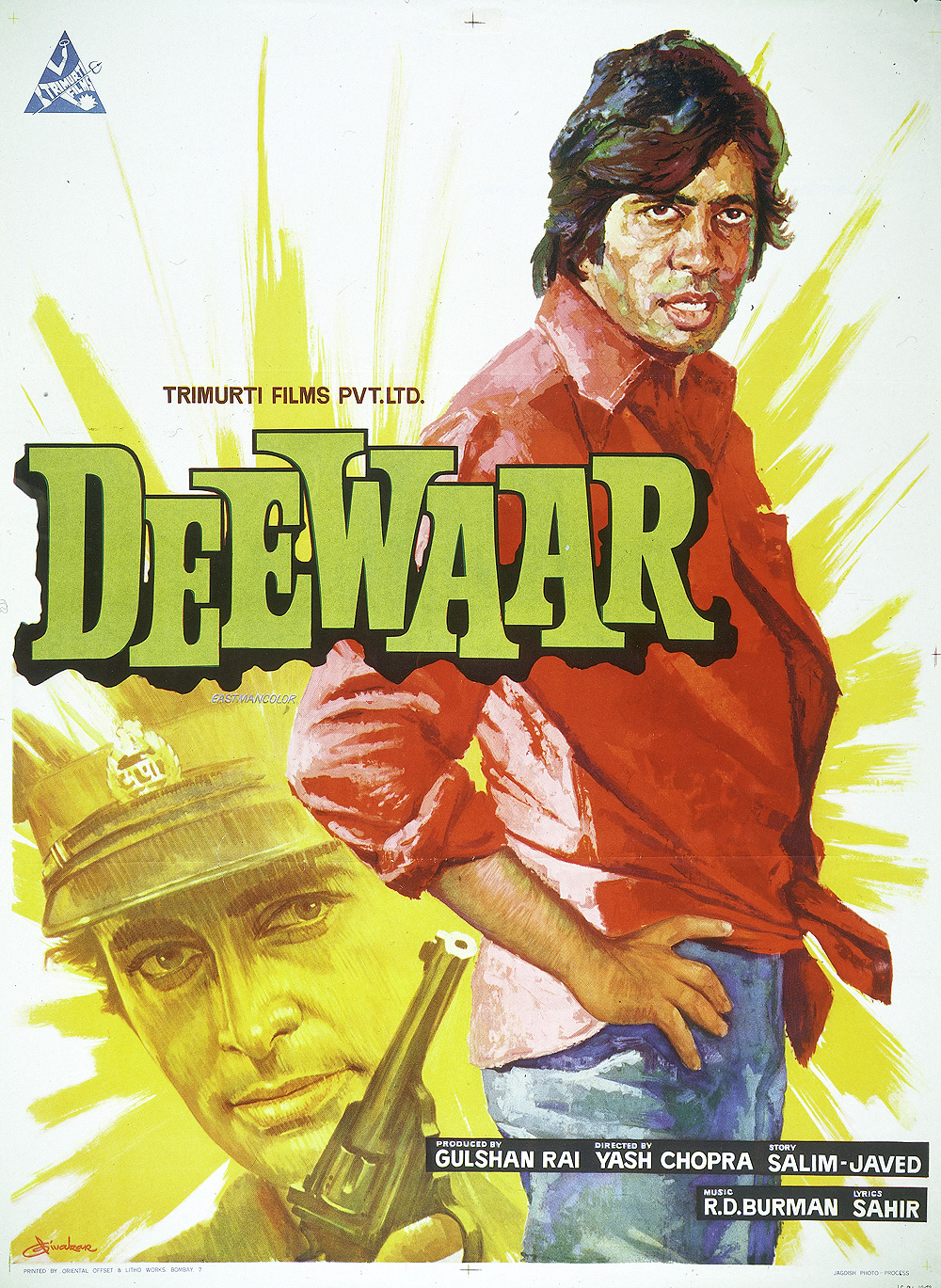

Amitabh Bachchan’s tryst with action was a major highlight of the 1970s, represented with some creativity in posters of films like Zanjeer ("Chain;" Prakash Mehra: 1973), and Don (Chandra Barot: 1978). These posters generate a sense of the kinetic through body movement, agility with guns and a mise-en-scene of violence, establishing Bachchan as an action hero. Zanjeer is the film that catapulted Bachchan to fame, even as he was the fourth choice for the lead role.10 Written by Salim Javed, Zanjeer is a straightforward revenge film based on the childhood trauma of a young Vijay (Bachchan) who witnesses his parents’ murder. Two posters of Zanjeer (figs. 02 and 03) display all the major characters of the film, but the themes of anger and action have a centrality that becomes a recurrent motif in other Bachchan posters. This was thus, the first film to display the iconography of anger that marked Bachchan’s stardom in the years to come.

A low budget film that ended up becoming a huge success at the box office, Zanjeer was subsequently re-released. As evidenced by the caption on the posters, “Prakash Mehra’s smash hit now in cinemascope,” these are obviously re-release posters of the film designed after a new cinemascope version was created to add to its value. The change in projection technique is highlighted in the poster as an additional attraction. The caption also makes it clear that the producers were capitalizing on the success of the star after a series of hits and re-released the film with a new print blown up to cinemascope. In the days before the arrival of the VCR, the re-release of films was a major source of revenue for the film industry and was always accompanied by a new set of posters. Additional information is therefore added to the Zanjeer poster for the film’s re-release.

1 See Sara Dickey, “Still One Man in a Thousand,” and Rosie Thomas, “Zimbo and Son Meet the Girl with the Gun," in David Blamey and Robert Desouza ed., Living Pictures: Perspectives on the Film Poster in India. London: Open Editions, 2005, 27-44 and 69-78. Also see R. Srivatsan, “Looking at Film Hoardings: Labour, Gender, Subjectivity and Everyday Life in India,” in Public Culture, Vol.4, Number 1, Fall 1991, 1-23.

2 For a detailed account of the production, design and technological transformation of posters in India, see Ranjani Mazumdar, “The Bombay Film Poster,” in Seminar, Vol. 525, May 2003, 33-41. Also see Rachel Dwyer and Divya Patel, Cinema India: The Visual Culture of Hindi Films New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2002, 101-183.

3 Ibid.

4 Madhava Prasad, The Ideology of the Hindi Film: A Historical Reconstruction, New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1998, 117-159; Vijay Mishra, Bollywood Cinema: Temples of Desire, Routledge, 2002; Ranjani Mazumdar, Bombay Cinema: An Archive of the City, Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2007, 1-40; Sushmita Dasgupta, Amitabh: The Making of a Superstar, Penguin Global, 2007; and Valentina Vitali, Hindi Action Cinema: Industries, Narratives, Bodies, New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2008, 184-229.

5 Avijit Ghosh, “India’s Journey with Amitabh Bachchan” The Pioneer, November 24, 1996. The term “JP movement” refers to the powerful movement of students and youth against government corruption led by the Gandhian Jayaprakash Narayan, particularly in the states of Bihar and Gujarat. During this movement, Narayan gave a call for peaceful “Total Revolution”. The JP movement was a significant opposition to the Central Government in power and Indira Gandhi, the then prime minister, responded by arresting Narayan and thousands of activists, finally imposing a state of National Emergency. For more on the JP movement, see Francine Frankel’s India’s Political Economy 1947-77: The Gradual Revolution New Jersey, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1978 and Bipin Chandra’s In The Name of Democracy: JP Movement and the Emergency Penguin Books, India, 2003.

6 In interviews with script writers Salim Khan, Javed Akhtar and Javed Siddiqui and directors Ketan Desai and Mahesh Bhatt, the term “complete actor” constantly came up during discussions to refer to Amitabh Bachchan. It was also widely used in Screen and the Trade Magazines, Film Information and Trade Guide. Komal Nahata, the editor of Film Information was the first to explain the concept to me. It is rumored that the French filmmaker François Truffaut first used it for Bachchan. All interviews conducted in Bombay, July, 1995.

7 Quoted in Udaya Tara Nayar, “Amitabh Bachchan Superstar” Indian Express, June 24, 1984.

8 Vijay Mishra, Bollywood Cinema: Temples of Desire, New York: Routledge, 2002,130.

9 Tarun Tejpal, “The Mirror has Two Faces,” Outlook, July 20, 1998.

10 Interview with Javed Akhtar, Bombay, April, 2003. Raj Kumar, Dev Anand and Dharmendra were the other actors approached for Zanjeer.

You May Be Interested IN